Author: Trica Oshant-Hawkins, AWF Conservation Programs Director

Author: Trica Oshant-Hawkins, AWF Conservation Programs Director

Centennial Spotlights

This winter, AWF is kicking off a full year of celebrating our 100 year anniversary: Our Centennial! Along with a series of special events and activities, we will be sharing our amazing history with you in the form of “Centennial Spotlights” – articles on the people and events that made the Arizona Wildlife Federation what it is today. We stand on the shoulders of giants and we want to share their stories and contributions with you. These are stories worth telling and people worth remembering for what they have done not only for AWF but for Arizona wildlife. As we look ahead to our next 100 years, we honor those who laid the foundation for AWF and science-based wildlife stewardship in Arizona.

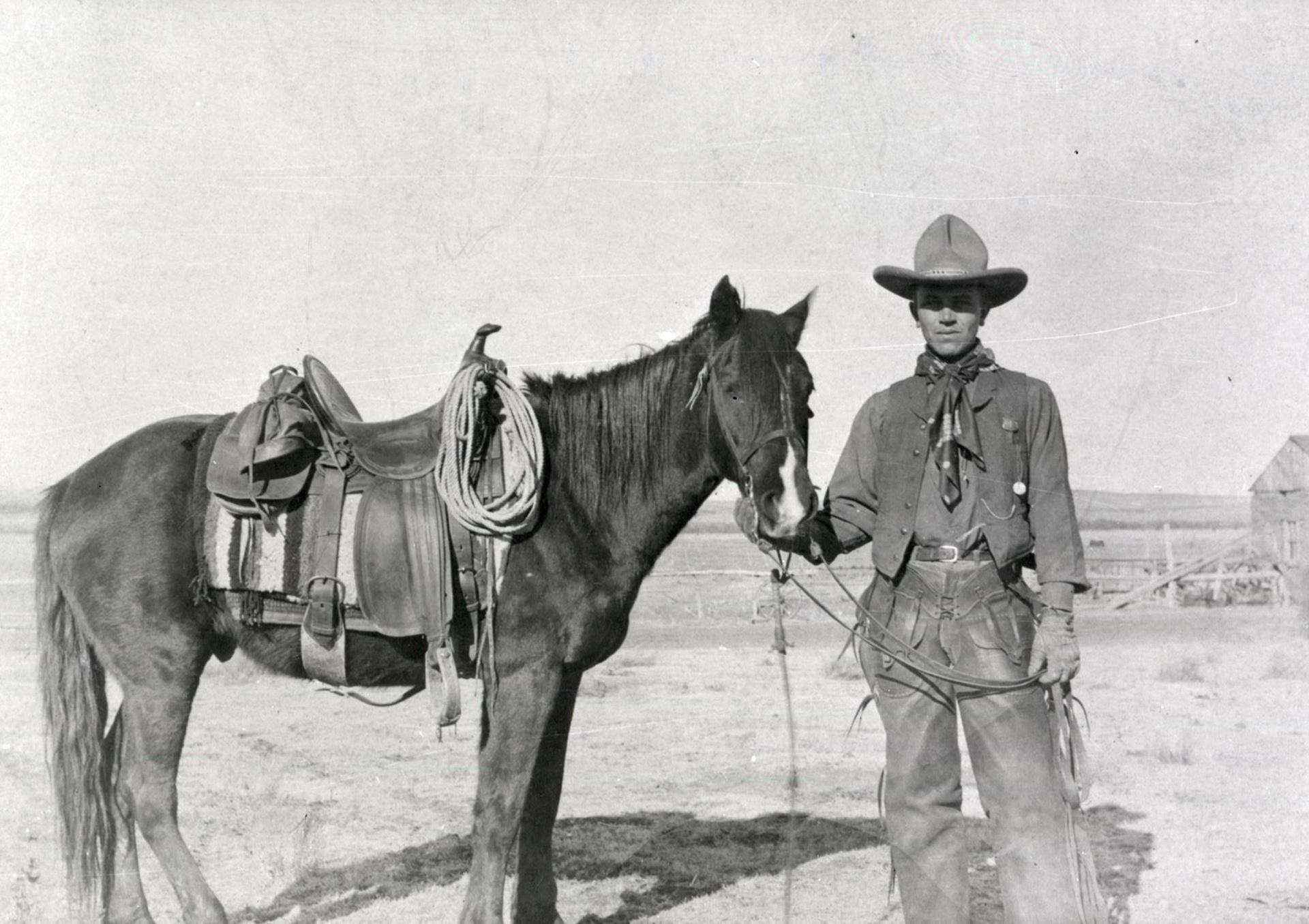

Centennial Spotlight: Aldo Leopold and the Formation of the Arizona Game Protective Association

Aldo Leopold is a name very familiar to most people who know and love wildlife. He is considered to be the “father of wildlife conservation.” But few know of the impact that Aldo had on Arizona wildlife, and the role he played in the establishment of the Arizona Wildlife Federation. While he is perhaps best known for establishing the country’s first wildlife ecology program at the University of Wisconsin and restoring his family’s severely degraded parcel of land in the Wisconsin countryside (all documented in his seminal book, A Sand County Almanac), Aldo actually spent his formative professional years in the Southwest.

In 1909, following his graduation from Yale University, Leopold took a job as Forester on the newly minted Apache National Forest in the Arizona territory. Given his work ethic and

practical intelligence, Aldo quickly moved up the ranks to the position of Forest Supervisor for Carson National Forest in New Mexico. During his time in the Southwest, Leopold spent many hours in the field documenting wildlife and vegetation, and noting changes in the landscape. He was also witnessing firsthand, an obvious decline in habitat quality and wildlife populations. It was during these early years in the Southwest that Leopold avidly participated in eradication efforts of many predators. At that time, it was believed that (as Aldo put it),

“because fewer wolves meant more deer, no wolves would mean hunter’s paradise.”1

But it was also here that Aldo began learning his greatest lessons. He came to understand that all animals play a role in the balance of nature, and wolves and other predators are necessary for a healthy ecosystem. He began to see nature in the balance of nature, and wolves and other predators are necessary for a healthy ecosystem. He began to see nature as a community of interacting living organisms. He began to develop a land ethic.

As Aldo was internalizing these lessons, it was becoming clearer to him that wildlife needed to be managed scientifically. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, where Aldo was stationed at the time, he organized a statewide organization to address this issue by rallying and assembling a group of sportsmen. Together, they formed the New Mexico Game Protective Association (NMGPA), an affiliate of the American Game and Propagation Association, which had been recently formed in New York in response to the “rampant slaughter of game in the absence of state and federal laws.”2 The year was 1916 and wildlife populations were at all time low across the country. Many species were in danger of extinction or already extinct.

Like New Mexico and the rest of the country, Arizona was experiencing the same issues of declining wildlife, and had minimal wildlife regulations. It was also clear that wildlife were primarily being managed through the whims and desires of politicians.

That same year (1916), a group of 35 sportsmen convened in Flagstaff, Arizona and formed the Flagstaff Game Protective Association.3 Aldo Leopold was at this meeting, having helped rally these Arizonans to the cause. It wasn’t until October, 1923, however, that the statewide Arizona Game Protective Association (AGPA) was formed, following in the footsteps of New Mexico. Again, Aldo Leopold was there to guide and assist.

The primary objectives of AGPA were to:

• Secure proper and scientific management of our fish, wildlife, and other resources in perpetuity for the full enjoyment of Arizonans;

• Secure a game and fish commission and department, the same to be sufficiently staffed with competent personnel free to work without political obligation or interference;

• Give that commission broad regulatory powers to enable them to accomplish their purpose; and

• Educate the public with the principles of sportsmanship and the need for proper resource management.

That first meeting of AGPA marked the beginning of true game management in Arizona. The tide did not turn over night however and many worked tirelessly over the years to ultimately ensure that wildlife are managed scientifically, competently, and without political influence.

As the Arizona Game and Fish Department and Commission matured, the need for the formative and oversight focus of AGPA shifted. In 1951, AGPA affiliated with the National Wildlife Federation and became the Arizona Wildlife Federation. Today, AWF’s mission remains very close to when it was the AGPA, stating that “AWF is dedicated to educating, inspiring, and assisting individuals and organizations to value, conserve, enhance, manage, and protect wildlife and wildlife habitat.”

Coupled with its mission, advocacy has been a hallmark of AWF throughout its history. For nearly 100 years, following in Aldo’s footsteps, AWF has successfully rallied supporters and forged common ground among opponents. As a result, AWF has been instrumental in issues regarding public lands protections, the right to hunt and fish, improvement of outdoor recreation and wildlife habitat, the enforcement of state and federal conservation laws related to fish and wildlife management, and other legislation that impacts Arizonans’ opportunities to enjoy the great outdoors.

Although Aldo Leopold left the Southwest in 1928 to live and teach in Wisconsin, his legacy remains very real and present here. We are proud of the role that Aldo, the father of wildlife conservation, played in the formation of Arizona’s first and oldest conservation organization, the Arizona Wildlife Federation. Indeed, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

1. Aldo Leopold. 1949. Thinking Like a Mountain in A Sand County Almanac. Random House.

2. John Crenshaw. 2003. A Century of Wildlife Management, Part 3. New Mexico Wildlife (Vol. 48 No. 2).

3. David Brown. 2012. Bringing Back the Game: Arizona Wildlife Management 1912-1962. Arizona Game & Fish Department.

.png)